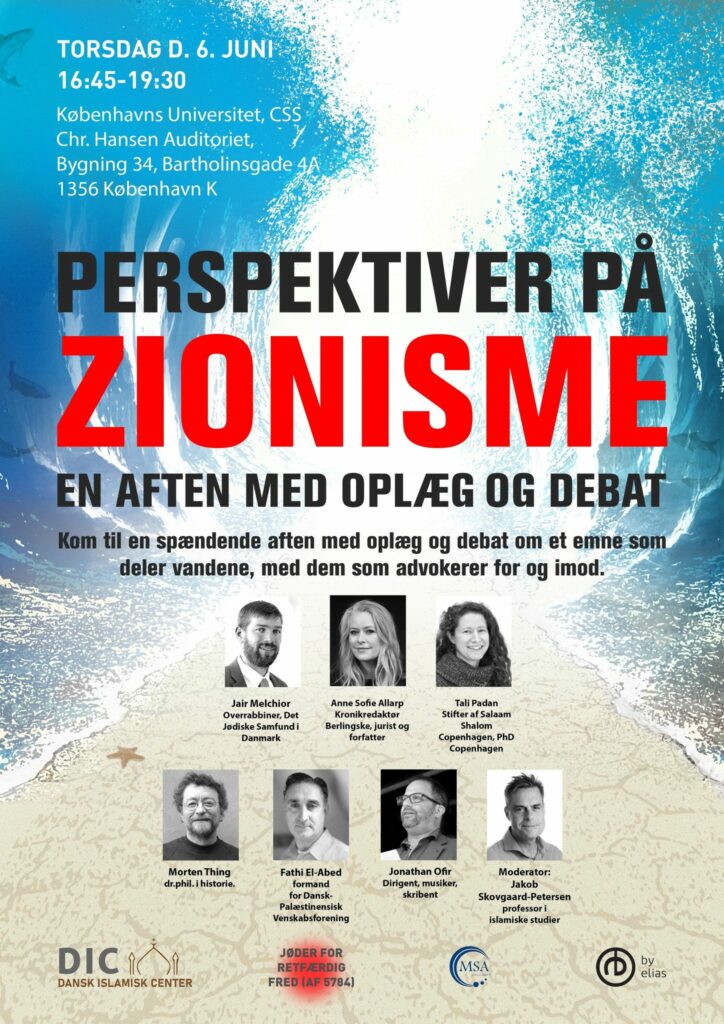

I was invited to speak on a panel about Zionism. Those who know me and my work may find it strange that I would speak on such a panel, but the organizers wanted to include diverse perspectives. It takes somewhat of a risk to do this, and I appreciate their openness.

In my talk, I shared that I would not speak about Zionism, as content, but speak about the ways in which we engage in the debate about Zionism, which I claim is just as important to the learning process. I introduced the concept of dissonance, the clash between old and new perspectives, and our natural inclination to reduce dissonance so that we can stay in the comfort of our own worldview.

I shared the value of lingering in dissonance through a personal example of my own dissonance. Around ten years ago, when I first moved to Denmark, I found myself in a very unstable and dissonant state. Because I was in this state, I was able to open up and ask questions about stable knowledge that I grew up with.

It was during this time that I attended a talk about Gaza and found myself upset by the difficult pictures of wounded and dead children. I asked the presenter why he was only presenting one side, which was my way of trying to reduce my experience of dissonance. We sat and talked for several hours after that, and I realized that there was a lot I was missing in my upbringing in terms of understanding the suffering of the Palestinians in the last 70+ years.

With this new knowledge, I started to attend demonstrations and post on Facebook these new perspectives, hoping that my Jewish family and friends in Israel and the US would also come to understand this new world that I had just been exposed to. But it doesn’t quite work that way. The opposite happened. People, my family included, started getting very upset at these posts.

Again – dissonance. After struggling for some time trying to reduce this dissonance by trying to win arguments (an endless game with no winners), I decided to try something different. After all, how could I claim to be fighting for peace when I am in conflict with the people I love most? So instead, I worked more deeply to understand where they were coming from. Second and third generation from the Holocaust, they see Israel as a place of security and belonging. They carry the fear of not having a safe space. All of these are just as real.

I explained to the audience that when people share views that are anti-Zionist, many Jews and Israelis do not hear that as an attempt to reshape the demographics of Israel/Palestine while keeping both sides safe and in peace. People hear that as an attempt to erase them, to wipe them off the map. No amount of ‘but that’s not what I mean’ will help.

Out of this grew my passion for sitting in circles. Not only to share and be cozy but to really work through democratic processes and invite dissonance. By reflecting on the ways in which we try to reduce dissonance, we can open up to new perspectives – not just understand them cognitively but take them in as our own, a big difference. This is an opposite force to polarization.

At this point, I was running out of time and stumbling around in my broken Danish, but if I could have continued, I would have shared a bit more about my PhD research and the results of my study. As I studied these circles, I found that dissonance can lead us down two paths. You can choose to reduce dissonance, which gets easier and more automatic as you hang out only with people you agree with and watch media that confirms what you think. OR you can reflect on dissonance reduction strategies and allow new perspectives to come in to your experience, a process opposite to polarization, of inclusion and integration. With practice, you can also get better at this skill.

Ultimately, I take it for granted that we want things to change. We want the war to stop. We want peace and security for all sides. In order to change, we can’t keep throwing our opinions at each other. After hearing the rest of the panel and the boos and claps of the audience, I had to ask the audience –

Are you really here to learn? Or just to confirm what you already know? And that goes for both ‘sides’.

I stayed quiet for the rest of the conversation because it was the usual back and forth of trying to win a debate. For some, it might have looked weird that I was the only one not participating. The moderator tried to bring me in, but I could not really connect to the question, and we were already too deep in the debate format.

A man came up to me after the talk and asked ‘why are you here?”. I tried to explain that if we want to learn about a topic, we also have to look at the things blocking us from learning. He asked again, ‘yeah but why are you here?’. This was not an attack, he genuinely was trying to understand the relevance of my perspective. It was as if he was saying ‘we’re trying to argue here, why don’t you have an opinion?’

You could say the event was disappointing because of this endless back and forth. But you could also say that it was inspiring. Because it exposed an absurdity. I have over ten years of expertise in dialogue processes and even longer as an educator. In an event with the supposed aim of learning, I shared what can help us learn. And, it is difficult to figure out why I am there.

This is not a critique on the panelists or the organizers, but this is a reflection of the world we live in. As more and more power structures get exposed, globally and personally, we can see how the power method just does not work. Trying to win a debate will not help to understand Zionism, nor will it help to achieve the things that I believe, in our hearts, all of the panelists wish to achieve. We just couldn’t get to that place, in the debate format.

To be fair, a few lovely people came up to me after my talk and could really see the relevance. These are also our warriors… mostly soft-spoken but fierce with their commitment to freedom and peace.

My 3 year old son looked up at me this morning with his big curious eyes and asked, ‘Mama, what does love mean?’.

I couldn’t answer him. Some things you have to show and not tell.